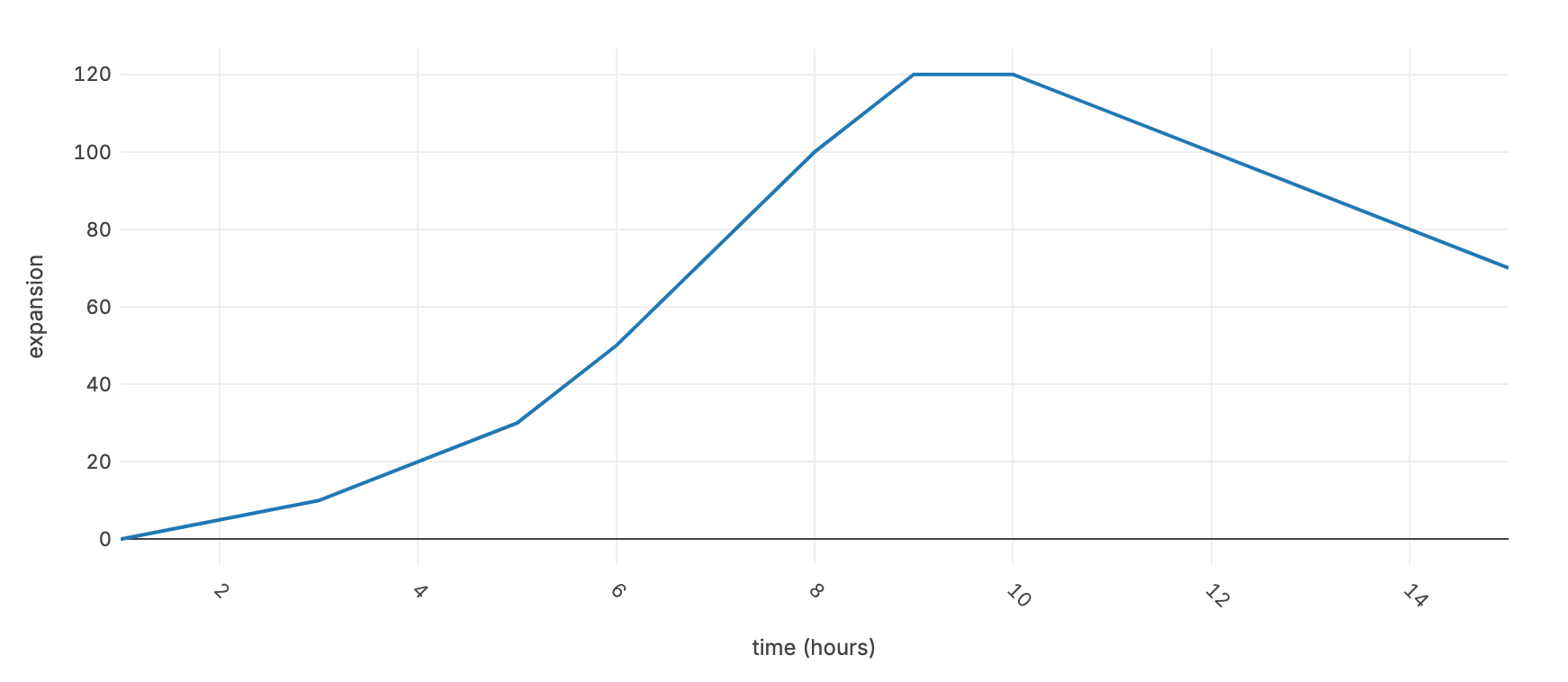

This experiment examines the shaping of the dough earlier or later in the leavening process. Rising dough – aka fermentation – can be represented as an upward trending curve on a graph, with dough expansion on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. The line starts flat, becomes increasingly steeper, then flattens again and then slowly tends downwards as the dough “deflates”. (Ideally the dough is in the oven or refrigerator before the curve flattens.)

(Fictional graph data to illustrate idea – not a real dough expansion series)

The goal of this double-bake experiment is to evaluate the impact on crumb, loaf height, and bloom score of ending bulk fermentation at different points on the curve. The total fermentation of the two doughs is the same, but one dough has a shorter mass fermentation and a longer final proof and the other a longer mass fermentation and a shorter final proof.

It is important to understand that the results and conclusions of this experiment (how far you want to push the fermentation during each leavening phase) may not be applicable to other flours, dough hydration and temperature, and handling (method development and modeling of gluten). For example, a dough made from low-gluten flours is less capable of retaining large, elongated bubbles in its structure, so it may appear flatter than a high-gluten dough with the same degree of fermentation. This is to say that this same experiment was done All red fife wholemeal flour would probably be higher if shaped and baked with less dough expansion. Meanwhile, a bread flour dough, or a much drier dough, could be shaped earlier and risen longer and still hold its shape.

Previously modeled (left); modeled later (right)

Method

Baker percentages

62% bread flour

38% red fife whole grain flour or house-ground red fife wheat berries

75% water

Mother yeast 12.5%.

1.8% salt

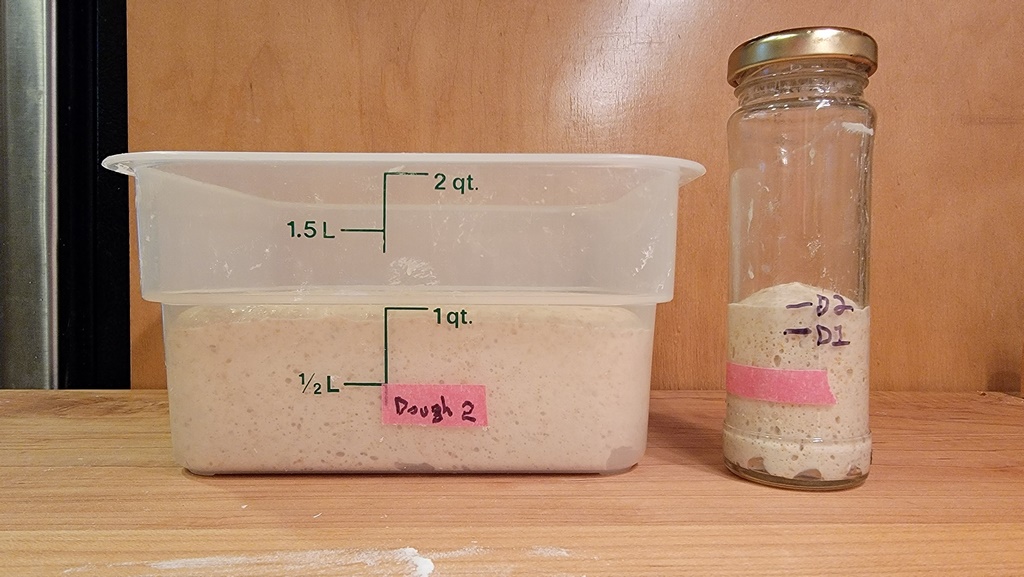

The double batch of dough in this experiment contained 500 grams of bread flour and 300 grams of red fife wholemeal flour. After thorough mixing it was divided into two straight-walled buckets and an aliquot jar to monitor the total expansion of the dough from the dough to the oven.

The word “aliquot” means a sample or part of a whole. In the context of baking bread, it is a small portion of a larger dough that you place in a small straight-sided container after mixing. After marking the initial level of the aliquot, you can monitor its expansion to decide when to shape and bake the main dough. If other variables are held constant, over the course of multiple bakes it is possible to evaluate how different levels of expansion in the aliquot container affect the final loaf.

Immediately after mixing

The doughs were subjected to two cycles of stretching and folding during the first hour of bulk fermentation, and everything was stored in a proofer at 77°F.

Time to shape dough 1 (60% expansion)

Time to shape dough 2 (90% expansion)

Interestingly, the expansion of the dough aliquot lagged behind the expansion of the bread doughs in their buckets, perhaps because all the dough started at 80°C and the aliquot cooled faster to the temperature of the prover of 77°F due to its lower thermal temperature. mass. The temperature of all three was the same about 50 minutes into a 7 hour process (oven mixing), so this discrepancy remains a bit of a mystery.

Dough 1 had a shorter bulk fermentation and was formed with 60% expansion (40% aliquot expansion).

Dough 2 had a longer bulk fermentation and was formed with 90% expansion (60% aliquot expansion).

The doughs were delicately shaped and did not have pre-forming and resting on the bench. They were put in the oven when the dough portion had an expansion of 80%. Looking at the difference between the baskets and the rate, the total expansion of the dough at oven time “in terms of baskets” was probably 120%.

Results

Dough 1, on the left, had the shortest bulk fermentation and the longest final proof. This bread has a more attractive honeycomb crumb, but is flatter with less bloom.

Dough 2, on the right, had a longer bulk fermentation and a shorter final leavening. This bread has a less uniform crumb with some narrower areas and some larger holes, but it is taller and has more bloom.

Conclusions

This experiment demonstrates that shaping at quite different times on the fermentation curve can produce good loaves of bread. Depending on your goals, you can play with the timing, as well as adjust other aspects of the process, to achieve different crumb and loaf heights.

For this combination of flours and with this hydration, the next time I bake, I might repeat the times for dough 1, but try adding a preform and a rest on the bench in hopes of strengthening the shape for a longer final test. Or I could finish the bulk fermentation between dough times 1 and 2, with 75-80% expansion, and gently shape again without preforming. To get to this same total fermentation of the dough I would need to use an aliquot jar again and evaluate again how it expands compared to the main dough.